The Yemenis spoke a Non-Arabic language. I thought the video I shared and Shimbiri's post which you claimed to not contradict your beliefs already established that. So if Yemenis populated Hejaz and taught their languages to Ismael and his sons, the prophet ﷺ and Quraysh would've spoken South Semitic language like today's

Mahri. Obviously, this was not the case and the minority Yemeni migrants were absorbed by the more numerous Northern Arabic speakers.

There were actually more migrations from the North to the South instead of the vice versa. The earliest Inscriptions of the Arabic languages are found in Syria, Jordan and then in Northern Arabia, this indicates Southern movement of the earliest Arabic speakers.

The ancient Yemeni languages are more related to the Ethiopian languages like Amharic and Tigray than Arabic. It's not possible for Arabic to evolve from distantly related language like the ancient South Arabian ones.

You are completely wrong. The video shimbiris posted has nothing to with old South Arabian.

Arabic tribes can’t have come from the north because the dominant FGC11 has its highest diversity in the south in what’s now Yemen. Graffiti up north doesn’t mean much.

This is what a Semitic language Jewish student named Agamemnon who is quite knowledgeable told us and I quote

“South Semitic is an antiquated grouping which is almost entirely discarded nowadays except by a few diehard mohicans. Beyond geographic proximity, the features most commonly used to justify the classification of Arabic, Ethiosemitic and MSA together are:

- Broken or internal plurals as the main pluralisation strategy in those languages, as in Arabic عَـام ˁām "year" > أَعْـوَام ˀaˁwām"years" and Ge'ez ቤት bet "house" > አብያትˀabyāt "houses".

- The presence of a verbal stem (L-stem or conative stem) formed by insertion of a long vowel between the first and second radical as in Arabic قَـاتَـلَ qātala "to combat".

- Shift of Proto-Semitic */p/ > /f/.

The first two are retentions, not shared innovations, broken plurals for instance can be traced back to Proto-Afroasiatic and left traces in other branches of the Semitic family while the L-stem is also found in other branches of the Semitic family and isn't unique to Ethiosemitic, MSA and Arabic. Finally, the shift of /p/ to /f/ is cross-linguistically common, think of PIE

*pṓds > Proto-Germanic

*fōts "foot" for instance.

An updated version of the South Semitic theory simply excludes Arabic and Sayhadic as the arguments in favour of a closer genetic relationship between those and Northwest Semitic are infinitely more convincing (as they are mostly based on shared morphological innovations, including in the verb system) however the arguments adduced to support grouping Ethiosemitic and MSA together are just as problematic, which leaves us little choice but to interpret those as archaic West Semitic branches on equal footing with Central Semitic. That being said, some of the features used to support South Semitic as a valid genetic grouping are better understood as evidence of contact between Arabic and the pre-Arabic languages of the peninsula (more on that below, see my answer to Shamash).

It could be argued that the early Central Semitic migrants were more mobile than normally assumed, this of course depends on when and where the camel was domesticated. Based on osteological, pictorial and archeological evidence, we can be more or less certain this happened between 4,000 and 3,000 years ago, and most likely during the end of the second millennium BCE in the Levant. It seems likely that there were different epicenters for the domestication of the camel in SW Asia, one of which was in Mesopotamia, and there are grounds to suspect that the Umm al-Nar culture in SE Arabia was another early center for camel domestication (we also have evidence of wild dromedaries being hunted in Central Arabia roughly a thousand years before). In any case, those areas would not have been Central Semitic-speaking by that time (the Umm al-Nar culture for instance was preceded by the Hafit period, characterised by beehive tombs that are reminiscent of the Nawamis-type cairns in the Levant, which is bound to mark the arrival of the first Semitic-speaking groups in the area), nevertheless one might envisage a scenario where this enhanced contact of some sort.

Returning to the linguistic evidence, in my view we do have more than a few elements which suggest some sort of prolonged contact between the Proto-Arabs and the pre-Arab peoples of the Peninsula, I mentioned above some of the features usually cited to support the notion of a South Semitic branch uniting Ethiosemitic and MSA to Arabic (and Sayhadic as well), I'll keep this user-friendly but some of the features invoked point in the direction of intense contact between varieties of Old Arabic, Ethiosemitic, MSA, Sayhadic and other North Arabian languages instead of a straightforward genetic relationship. The internal or "broken" plurals for example, while those are a feature of Afroasiatic languages in general and aren't specific to the Semitic languages of Southern Arabia, the sheer productivity and nature of the patterns along which those are formed are not coincidental, notice for instance that in the two examples I've used (

ˀaˁwām &

ˀābyāt) the pattern is ˀaC₁C₂āC₃, this isn't an exception and those patterns are also present in other Ancient North Arabian languages. Speaking of those languages, yet another element I'd like to draw your attention to is the presence of innovations characteristic of Arabic in the non-Arabic languages of the peninsula, the following Dadanitic inscription (AH 203) is a pretty fitting example:

While Dadanitic, as far as we can tell, is not outstandingly similar to Arabic (beyond the fact that it is a Central Semitic language, somewhat archaic in nature as it retains h-prefixed causatives) in this text there is at least one innovation that is typical of Arabic, namely the complementiser

ˀn (Classical Arabic

أنَّ ˀanna) to which I would add the -a subjunctive which is what probably underlies the

ykn form here (parallel with Classical Arabic

أَن يَـكُـونَ ˀan yakūna). So two shared morphological innovations unique to Arabic, despite the fact that Dadanitic did not partake in those innovations. What are the odds that this inscription was made by someone who was familiar with an early variant of Old Arabic or spoke a dialect of Dadanitic influenced by Old Arabic? I'd say those are very high indeed. And this is but a single example, there are other examples of the sort, not only in Dadanitic (where the relative pronoun

ˀallatī, an innovation characterising the Old Hijazi dialect of Arabic, is also attested) but in Sayhadic as well (the negative particle

lm, also a Proto-Arabic innovation, is attested in the Amiritic dialect of Minaic).

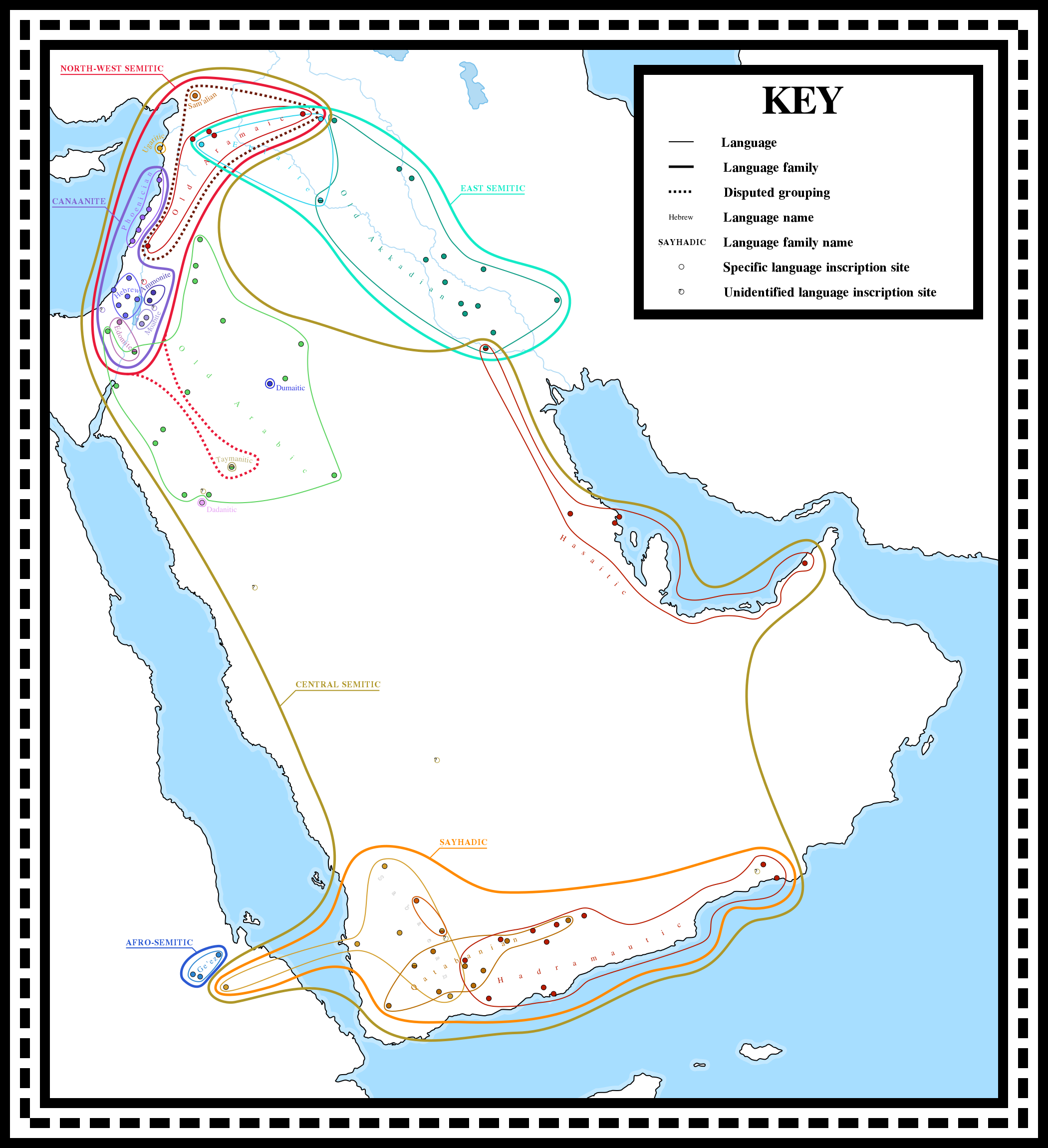

To picture the setting, here's a map of the Semitic languages consistent with genetic subgrouping:

Without complicating the matter further, the sum of the evidence (in conjunction with the genetic data) seemingly points towards the Central Semites being much more mobile than usually imagined (this would count for all sub-branches), and supports the existence of a sprachbund extending over much of Western Arabia comprising Old Arabic, Sayhadic, Ethiosemitic, MSA and possibly a few other Ancient North Arabian languages (including Taymanitic, which can be classified as NW Semitic). This further strengthens a 1st millennium (BCE) date for the initial introduction of Ethiosemitic in the Horn of Africa (it is otherwise hard to account for this type of prolonged contact), which is to put in parallel with the recent developments under P56. So a set of early back-migrations from Yemen cannot be discarded, and should probably be considered if more splitters show up in Yemen and its immediate surroundings”.